U.C. Berkeley’s Dr. Tolani Britton explores the link between anti-drug laws and college enrollment rates in a webinar with the SDP network.

U.C. Berkeley’s Dr. Tolani Britton explores the link between anti-drug laws and college enrollment rates in a webinar with the SDP network.

Two disturbing trends were emerging in parallel.

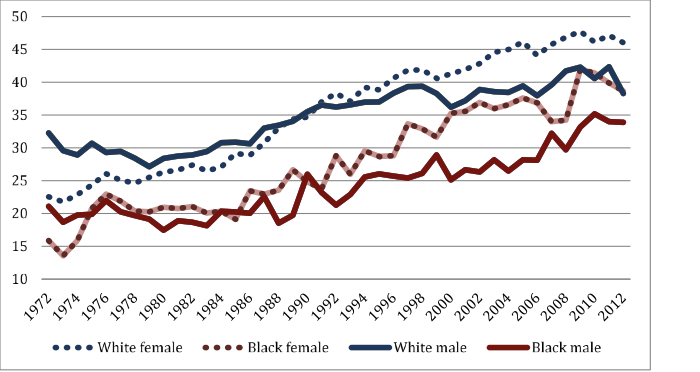

On one hand, gaps in college enrollment were growing by both race and gender. In 1972, U.S. colleges and universities saw similar enrollment rates between Black males and White females. Yet in the decades following the 1970s, enrollment numbers for Black males in particular began slipping, quickly falling behind all other groups, never to recover (see image below).

On the other hand, incarceration rates for this same group increased sharply during that same time period. Data on arrests from the FBI Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program revealed a disproportionate increase in arrests and incarceration of young Black men after 1986. Some named the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 as a culprit—this law instituted mandatory minimum sentences for drug possession and trafficking offenses, allowed law enforcers to seize the assets of those caught with illegal drugs, and increased funding for state and local drug control effects.

The concurrent trajectories of these two disturbing trends left Dr. Tolani Britton, Assistant Professor in U.C. Berkeley’s Graduate School of Education, wondering: Did the passage of this policy impact college enrollment for Black male students, and if so, was marijuana possession in particular at fault? She discussed her investigation of these questions with the SDP network in a recent webinar.

Do Drug Laws Explain Lagging College Enrollment?

To answer these questions, Britton used a difference-in-differences approach (the same approach used by SDP Fellow Moira Johnson in her literacy work in Fulton County) to compare changes in college enrollment between Black men and non-Black men/Black women over time. This approach assumed that if untreated (as in, without the implementation of a policy like the Anti-Drug Abuse Act), the college enrollment trends for each group would remain stable over time. It also assumed stable group composition over time.

“While traditional college-aged Black males were disproportionately arrested for drug possession and distribution infractions following the introduction of the federal law, it was unclear if these laws also had an impact on the likelihood of college enrollment for Black young men,” Britton wrote in “Does Locked Up Mean Locked Out,” the paper upon which the webinar was based. To try to reveal a connection between the policy and college enrollment, Britton then incorporated data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) October Supplement (1984-1992) and information on state and federal marijuana possession laws.

When first looking at the likelihood of college enrollment for male students aged 18-24, Britton found an overall ten percent decrease for Black men after 1986. This finding spoke directly to her first research question about the impact of the 1986 policy on Black males, yet it didn’t necessarily correlate with laws about marijuana in particular.

“After 1986, a number of states increased the minimum and maximum penalty for marijuana possession and distribution,” continued Britton. “Other states imposed mandatory minimum penalties for drug possession. As a result, Black and Latino young men were more likely to be arrested and incarcerated for drug infractions when compared to their White peers.” Thus, Britton speculated that in states with more punitive enforcement of marijuana laws, college enrollment rates for Black males would be lower.

Yet in these states, Britton only found a marginal decrease in college enrollment for this group. “This was surprising,” reported Britton. “With a rapid rise in arrest rates for marijuana possession, why wouldn’t we see more of an impact on college enrollment?”

What, if not marijuana?

Britton concluded that marijuana may not be the right drug of focus for this time period. “When thinking about the 1980s, the question was whether there was a more salient drug than marijuana. I then thought about the case of Len Bias, the college basketball player who died of a cocaine overdose just before the passage of the 1986 federal law and whose death some research suggests prompted the law’s inception. I then shifted my attention to cocaine laws and their enforcement in the same way I explored marijuana laws.”

While the effect of marijuana laws and their enforcement correlated to minimal decreases in college enrollment for Black men, the effect of cocaine laws correlated with a significant 12% decrease. This aligns with prior existing research that found that increases in incarceration rates led to decreases in high school graduation rates after the introduction of crack into local markets.

Britton’s work linking college enrollment decreases to policy highlights the systemic nature of racial disenfranchisement. “The question used to be hyper individualized. Historically we’ve asked ‘What did this person do wrong and do they deserve to go to college?’ Yet now we are recognizing the harms policies can inflict when applied unevenly or unjustly. We know the long-term benefits of every additional year of college, and those opportunities have generational impacts.”

We cannot think about improving education policy without improving social policy (and fair social policy enforcement) more generally. This research, along with other research working to reframe issues of police violence and strict disciplinary policies in schools, provides key insights for how to enhance the positive ripple effects of educational access and success. Those who are passionate about equity and closing opportunity gaps can also advocate in policy areas that impact the educational future of underserved students.

Watch Dr. Britton’s full webinar and read her full research paper.